What you’ll learn

- What the Saga pattern is (and what it is not)

- Why compensation matters for distributed transactions

- Multiple AWS implementations: orchestration, choreography, and hybrids

- Practical production tips: retries, idempotency, timeouts, DLQs, observability

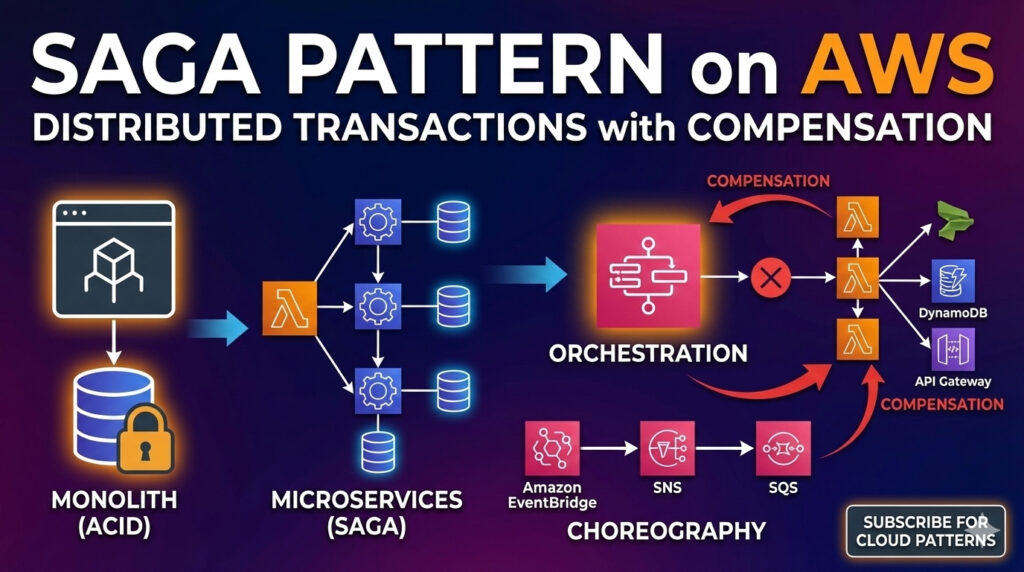

The problem: distributed transactions without a 2PC

In a monolith, you might wrap changes in a single database transaction. In microservices (or distributed systems), a single business action often spans multiple components:

- The order service writes an order.

- Inventory service reserves stock.

- Payment service charges a card.

- Shipping service creates a shipment.

You can’t easily use a single ACID transaction across multiple independent datastores and services (and you generally shouldn’t).

Saga is a pattern to achieve end-to-end business consistency using:

- A sequence of local transactions

- And, when something fails, compensating actions are taken to undo prior steps

Saga in one sentence

A Saga is a distributed workflow composed of local transactions, where failures are handled by running compensating steps to restore the system to a consistent business state.

Key idea: You trade strong, immediate consistency for eventual consistency with explicit recovery logic.

Two common styles of Saga

1) Orchestration (central coordinator)

One component coordinates the workflow, decides what runs next, and triggers compensations on failure. On AWS, the most common orchestrator is AWS Step Functions.

2) Choreography (event-driven)

There is no central coordinator. Services publish events, and other services react. On AWS, this is commonly done with Amazon EventBridge, SNS, and SQS.

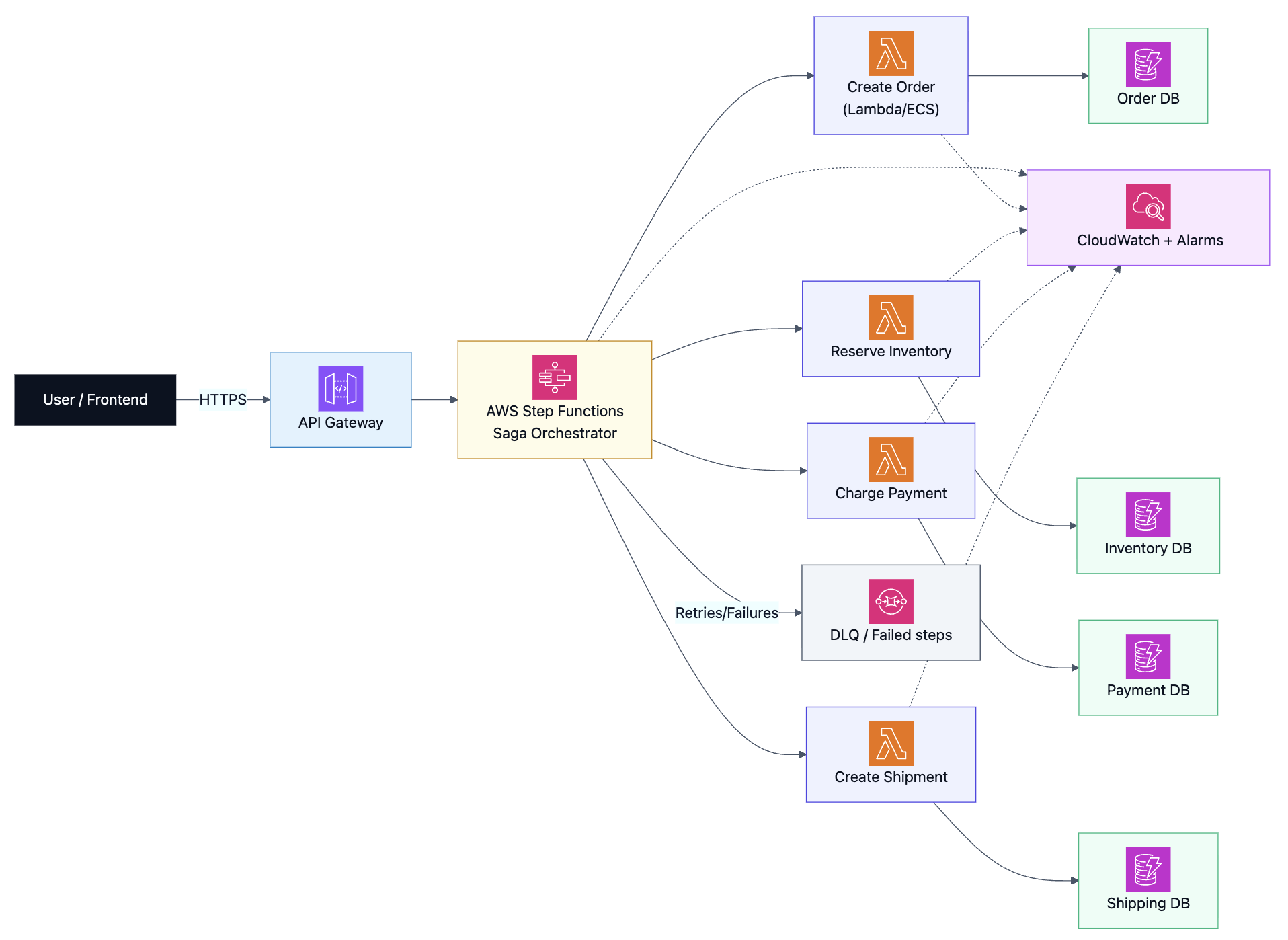

Option A: Orchestrated Saga with Step Functions (recommended starting point)

When it’s a great fit

- You want a clear “single place” to see the workflow

- You need long-running transactions (minutes/hours) with timeouts and retries

- You want explicit compensation logic and observability

High-level architecture (orchestration)

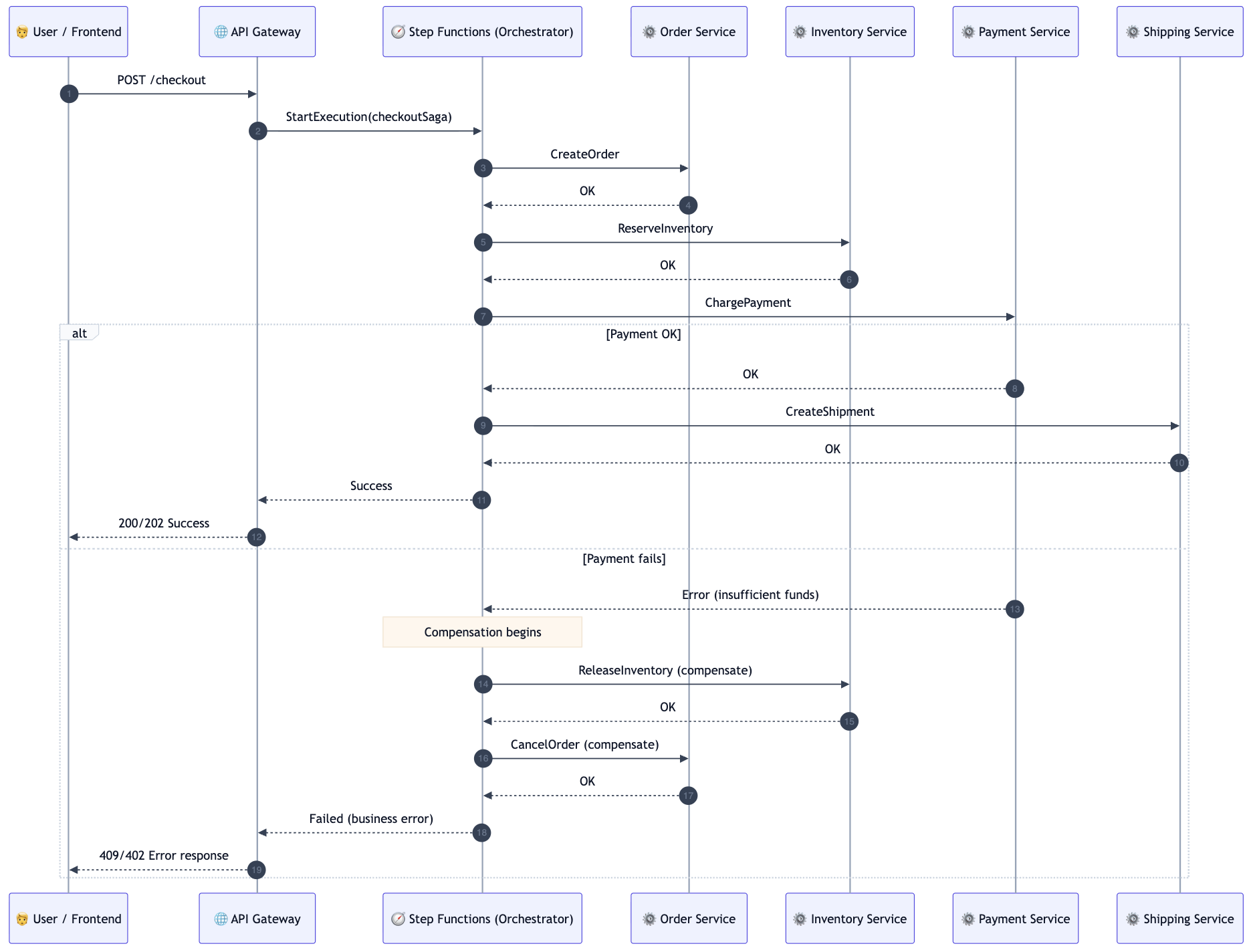

What compensation looks like (the core of Saga)

Each forward step should have a defined rollback (when rollback is possible):

- ReserveInventory → ReleaseInventory

- ChargePayment → RefundPayment (or VoidAuthorization)

- CreateShipment → CancelShipment

Some operations are not truly reversible. In those cases, your compensation is a business action:

- Notify a human

- Issue credit

- Create a “fix-up” task

Orchestrated Saga sequence (success + compensation)

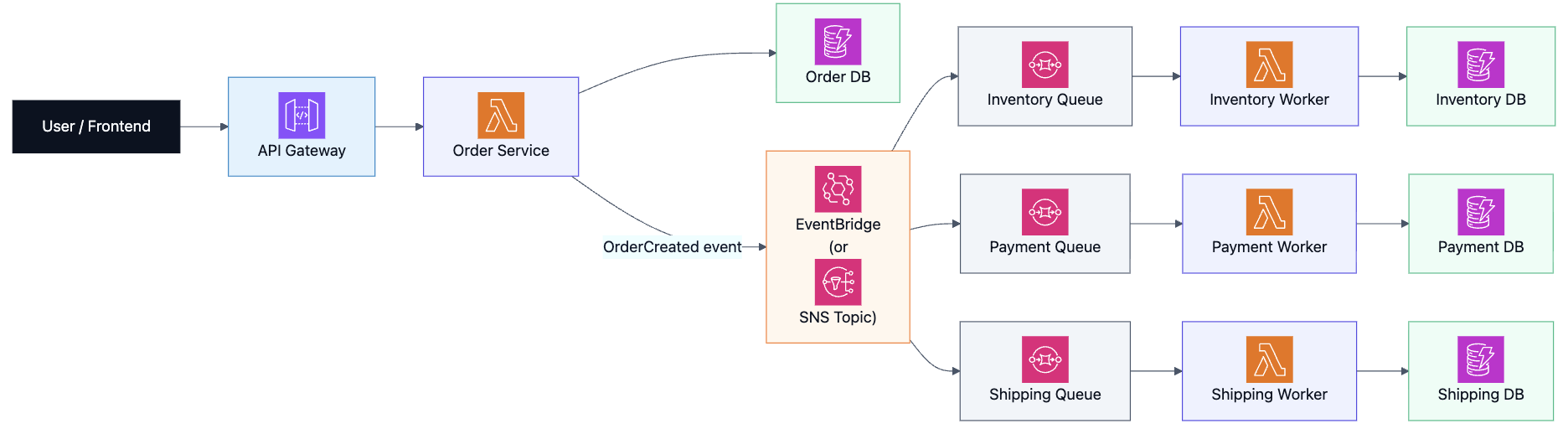

Option B: Choreography Saga (Event-driven with EventBridge/SNS/SQS)

When it’s a great fit

- You want each service to stay autonomous and “react to events.”

- Workflows are flexible and evolve often

- You want loose coupling (but accept more complexity in debugging)

Typical AWS building blocks

- Event bus: EventBridge (or SNS topics)

- Durable buffering: SQS queues per consumer (fan-out + backpressure)

- Workers: Lambda or ECS tasks

- Outbox pattern (recommended): ensure events are reliably published when the local transaction commits

Architecture (choreography)

How compensation works in choreography

Compensation is also event-driven:

- PaymentFailed → InventoryReleaseRequested, OrderCancelRequested

- ShippingFailed → RefundRequested, InventoryReleaseRequested

This style is powerful, but you must invest more in:

- Event versioning

- Replayability

- Observability and correlation IDs

Option C: Hybrid Saga (Step Functions + events)

Very common in real systems:

- Use Step Functions for the core “checkout” workflow

- Publish domain events (OrderConfirmed, PaymentCaptured) for downstream consumers

This gives you:

- a straightforward workflow for the critical business path

- an event-driven architecture for everything else

Production checklist

1) Idempotency everywhere

At least once delivery and retries are expected.

- Use an idempotency key per saga step (often

sagaId + stepName) - Make writes safe to retry

2) Timeouts and retries per step

Different steps need different policies:

- ReserveInventory: short retry window

- Payment: careful retries (avoid double charge)

- Shipping: longer timeouts (external providers)

3) Dead-letter queues and manual recovery

Have a “break glass” plan:

- DLQs for async consumers

- an operator dashboard or runbook to replay/fix stuck sagas

4) Observability and traceability

Minimum:

- log

sagaId,orderId,correlationIdeverywhere - CloudWatch alarms on failure rates and DLQ depth

- Use AWS X-Ray/OpenTelemetry for tracing where possible

5) Data model choice: prefer state machines over flags

Track a saga state explicitly:

- PENDING → INVENTORY_RESERVED → PAYMENT_CAPTURED → SHIPPED

- with timestamps and last error details for debugging

When Saga is the right tool

Use Saga when:

- You have a multi-step business process across services

- You can tolerate eventual consistency

- You’re willing to define compensation logic

Avoid Saga when:

- You truly need strict atomicity across multiple resources

- You can keep the transaction within a single service/database

Auto Amazon Links: No products found.